If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.

In mid-June, a court in Penza extended the arrest of several suspects in the so-called “Penza Case.” Nine left-wing activists from Penza and St. Petersburg are charged with creating a “terrorist group” that supposedly plotted to destabilize the country through a series of nationwide terrorist acts during the March 2018 presidential election and the FIFA World Cup. The case is based primarily on confessions extracted by federal agents, but several suspects say they were tortured into incriminating themselves. At Meduza’s request, Mediazona journalist Egor Skovoroda breaks down what you should know about the “Penza Case.”

Who’s been detained? What links the suspects? Why are prosecutors looking at their shared interest in the competitive team sport “airsoft”?

There are currently nine men now jailed in Penza and St. Petersburg who allegedly belonged to an anarchist “terrorist group” supposedly known as “Set” (Network). Federal agents detained five of these suspects in Penza in October and November last year, before arresting a sixth man in St. Petersburg and transferring him to Penza. In January 2018, officials detained another three suspects in St. Petersburg. At least two men living in Penza — Maxim Ivankin and Mikhail Kulkov — fled Russia and are now wanted by the police.

All suspects are men in their twenties, between the ages of 21 and 28. Not everyone knew each other before the arrests, but they did all share in common political activism and left-wing ideology (though only a few of the suspects are self-described anarchists or anti-fascists). All nine men are also fans of “airsoft,” a competitive team sport similar to paintball that uses plastic BBs. Some of the suspects were bigger fans of the game than others: firearms instructor Dmitry Pchelintsev, for example, organized airsoft tournaments, while Vasiliy Kuksov has only participated in a couple of practice sessions. Yuliy Boyarshinov, the last man arrested, is the only suspect who’s never played the game.

According to one of the defense attorneys, the case materials depict airsoft training sessions as the “illegal acquisition of forest survival skills and first aid skills.” The suspects’ combined interest in left-wing ideology and practicing airsoft in the forest is apparently what prompted their arrests. Several other activists in Penza who know the suspects but never played airsoft have been named as witnesses in the case.

What are the charges? Were they really plotting terrorist acts?

The evidence looks weak. In the case materials, for example, a memo from the Federal Security Service claims that the suspects intended to use terrorist attacks during the presidential election and the World Cup to “stir up the masses to destabilize the country’s political situation further,” supposedly leading to an “armed rebellion.” The FSB initially wanted to charge the defendants with planning an armed overthrow of the government.

The evidence available to the public contains no proof that any of the suspects planned terrorist attacks. In fact, the suspects aren’t directly accused of plotting any attacks — they’re charged with participating in a “terrorist group” whose aim, according to one witness, was to replace Russia’s “constitutional system with an anarchist system.”

The FSB says this group was divided into cells operating in Moscow, Penza, St. Petersburg, and Belarus, claiming that its members gathered several times for “congresses.” In St. Petersburg, the cells were supposedly called “Mars Field” and “Jordan” (also known as “SPb1”) and in Penza they were supposedly known as “Sunrise” and “5.11.” The suspects say these were just the names of their airsoft teams.

So what is the FSB’s evidence?

A gag order is in effect until federal agents complete their investigation and the case comes to trial. Given what we know so far, most of the evidence is based on confessions taken from the suspects during interrogation.

Formally, the entire criminal case is built on the confession of Egor Zorin, the youngest suspect in custody. Zorin went to school with Ilya Shakursky, who is probably the most prominent activist among the Penza defendants, known for his frequent anti-fascist events, lectures, and environmental protests. Zorin’s friends say the police detained him in the spring of 2017 on drug-possession charges, but he was quickly released. His friends believe this was when he may have started cooperating with the FSB.

The case materials also feature the suspects’ correspondence, videos recorded at airsoft practice sessions, and bugged conversations. In December 2017, for example, federal agents recorded a meeting between St. Petersburg suspect Viktor Filinkov and several of his friends at a McDonald’s, where the young people discussed “politics, training sessions in the forest, methods for detecting surveillance, cryptocurrencies, and the subway system.”

The FSB also bugged the Penza activists. When interrogating the suspects, investigators reportedly quoted excerpts from the young men’s conversations with friends. Federal agents even watched a brawl between Dmitry Pchelintsev and Ilya Shakursky (just a few days before the latter’s arrest), when the supposed terrorist-accomplices were fighting over a girl.

The FSB says its agents found a stash of weapons at the Penza homes of Vasily Kuksov, Dmitriy Pchelintsev, and Ilya Shakursky, and officers claim to have discovered a bucket of the bomb-making ingredients aluminum powder and ammonium sulfate at Arman Sagynbayev’s home in St. Petersburg. Kuksov, Pchelintsev, and Shakursky say the weapons were planted, noting that they were discovered in strange places (like inside a car without an alarm system).

Sagynbayev, on the other hand, has offered a full confession, his lawyer says, in exchange for certain privileges: access to his mother, the receipt of parcels containing food, and medical treatment for an unspecified “serious illness.”

Investigators found black powder (a low-power explosive common in pyrotechnics) at the home of Yuliy Boyarshinov, another Petersburger. Initially, he was only charged with illegal possession, but in April the FSB also named him as a member of the “Network” terrorist group. Boyarshinov has refused to testify, citing his constitutional right not to incriminate himself.

The FSB has also collected testimony from several witnesses, including multiple “secret witnesses,” whose role in Russian criminal justice often raises serious concerns. (Dmitry Bychenkov, a former suspect in the infamously politicized “Bolotnaya Square Case,” recently explained how secret witnesses are used in Russia.)

But we do know the names of some witnesses. On May 23, Russian guards at the Ukrainian border detained Victoria Frolova, one of the Penza suspects’ close friends. FSB agents from Penza later showed up in a black Priora and took her away for questioning. After a few days, Frolova managed to leave the country, but not before she was apparently forced to perjure her friends and sign statements where she named Shakursky, Kuksov, and Zorin as members of the “Sunrise” cell and Pchelintsev, Ivankin, Kulkov, and Andrey Chernov as members of the “5.11” cell.

The suspects are all young men. According to Viktor Filinkov, the activist recorded at a McDonald’s, federal agents told him that they were ordered to leave the girls alone — even the young women who played airsoft with the men who were arrested. “Only the guys will go behind bars,” an FSB agent allegedly told Filinkov. “Feminism is all well and good, but we see things a little differently. There was no order to bring in any of the girls.”

Why did the suspects confess? Is it because they were tortured?

Most of the suspects initially signed confessions, but they later recanted their testimony, saying that FSB officers had either tortured or threatened to torture them, when they first refused.

“They began to pull down my pants. I was lying on my stomach, and they tried to put wires on my genitals. I started screaming and begging them to stop. They kept saying, ‘So you’re the leader!’ To make them stop the torture, I said, ‘Yes, I’m the leader!’ They answered, ‘You planned to commit terrorist acts,‘ and I said, ‘Yes, we planned to commit terrorist acts,’” recalls Dmitry Pchelintsev, who says he was tortured in the basement of the Penza pretrial detention center.

Ilya Shakursky says he was tortured in the same detention center: “They attached some kind of wires to my big toes. I felt an electric shock and couldn’t help groaning and shaking. They repeated the treatment until I promised to say what they told me to say. From that time on, I forgot the word ‘No’ and said whatever the officers wanted.”

“He alternated shocks to the leg and shocks to the handcuffs. […] I caved almost immediately, within the first 10 minutes. I screamed, ‘Tell me what to say! I’ll say anything!’ but the violence didn’t stop,” says Filinkov, who gave an extremely detailed account of everything that happened to him after his arrest at Pulkovo airport.

The striking thing about the suspects’ accounts is how carefully calibrated their torture appears to have been. For instance, Filinkov recalls that he was taken for a medical examination before he was tortured. Pchelintsev says an FSB officer wearing white medical gloves stood by as he was administered electric shocks. The man supposedly checked his pulse several times during the ordeal.

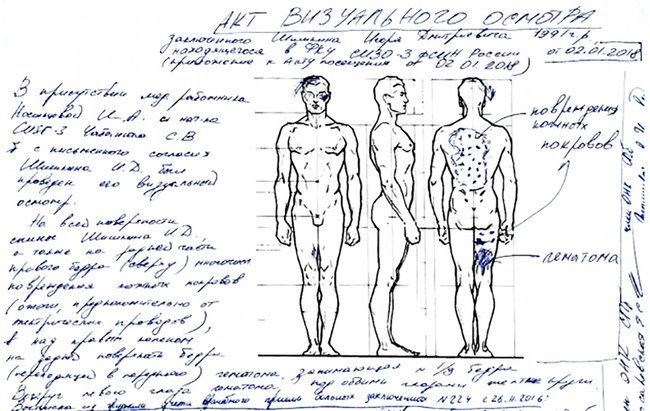

Igor Shishkin hasn’t accused police of mistreating him, but there’s evidence making it almost certain that he has been tortured in jail. Members of a public monitoring commission in St. Petersburg found what appeared to be burn marks from electric wires on his body, and doctors diagnosed him with a fractured eye-socket and multiple bruises and abrasions. At the FSB’s detention center, Shishkin signed a document stating that he sustained these injuries while working out.

Currently, only Shishkin, Arman Sagynbayev, and Egor Zorin say they’re guilty of the charges. It’s unknown if Zorin was also mistreated; he is the only suspect who’s been released from pretrial detention.

How have the Russian authorities responded to the torture allegations?

With total silence. The FSB apparently even mocked Viktor Cherkasov, Filinkov’s defense attorney, by answering his complaint with a perfunctory reply folded inside pages from a dressmaking magazine.

Russia’s Federal Investigative Committee refused to open a criminal case in response to Filinkov’s allegations, determining that federal agents had lawfully used an electric shock device against him, after Filinkov allegedly tried to escape from FSB custody. Filinkov says he wiped blood from his face with a hat after the beatings, and the hat could have provided material evidence against the FSB officers, but someone apparently stole it from him at the detention center.

Officials have also refused to investigate the alleged torture of Ilya Kapustin, who believes he was arrested simply because he knows Boyarshinov. The Federal Security Service eventually released Kapustin and named him as a witness in the “Penza Case,” but not before torturing him with electric shocks in the back of an FSB van, he says. Justifying their decision not to pursue Kapustin’s claims, investigators cited a doctor’s report stating that the marks on the young man’s body looked more like bed bug bites than wounds from electric shocks.

State prosecutors and human rights commission officials visited Pchelintsev after he claimed to have been tortured, but he told them that he’d lied about the mistreatment “to evade criminal liability.” Before long, however, he recanted this statement, explaining that he’d been threatened with more torture, if he didn’t tell the visitors what the FSB wanted him to say.

While the torture allegations never led to any criminal charges, the FSB apparently stopped mistreating the “Penza Case” suspects after human rights officials got involved.

In April 2018, the television network NTV aired a 30-minute exposé called “Dangerous Network” that featured footage from airsoft training sessions taken from the “Penza Case” materials. The video also included a pixelated interview with someone claiming to have been involved with the “terrorist group” (presumably Yegor Zorin). The broadcast referred to the “Penza Case” suspects as dangerous radicals, claiming that their attorneys are supported by foreign grants.

NTV‘s film also included edited CCTV footage from a pretrial detention center, showing Dmitry Pchelintsev smashing a toilet lid and trying to cut himself with the shards, while guards spend “a solid hour trying to bring the prisoner to his senses.” “Dangerous Network” implies that this behavior refutes Pchelintsev’s torture allegations against the FSB, supposedly proving that he injured himself.

Pchelintsev had already told his lawyer about this incident, saying at their first meeting that he’d smashed a toilet lid and cut himself on the arms and neck to force the FSB to stop torturing him. “There was blood from the cuts all over my clothes and the floor, and I collapsed. Prison officers must have seen me through the CCTV in my cell. They entered and gave me medical assistance,” Pchelintsev said.

The mothers of Ilya Shakursky and Arman Sagynbayev say an FSB investigator named Valery Tokarev blackmailed them into talking to NTV’s film crew. Mikhail Grigoryan, who was then acting as Shakursky’s defense attorney, also spoke to the TV network, surprisingly admitting that the FSB had proved his client’s guilt. Afterwards, Shakursky immediately fired his lawyer, and his mother later filed a complaint against Grigoryan with Russia’s bar association.

Pretrial detention center administrators tried to convince the suspects to grant interviews to the government-run network RT, but the men refused.

Is this situation unique? Has Russia witnessed similar cases?

The “Penza Case” recalls an infamous trial against “Crimean terrorists” in May 2014, when federal agents arrested four activists opposed to Russia’s annexation of the peninsula. According to the FSB, the suspects belonged to a “terrorist group” created by the Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov. These men also said Russian officials tortured them in jail, and in the end the “Crimean terrorists” were sentenced to between seven and 20 years in prison. Sentsov is currently incarcerated in Siberia, where he’s been on a hunger strike for more than a month, demanding the release of all Russia’s “Ukrainian political prisoners.”

Unlike the “Penza Case,” the investigation in Crimea came after two actual arson attacks: one against the Crimea Russian Group’s office, and the other against the political party United Russia’s office. The total damage in both these incidents was a burned door and window. According to the FSB, this was terrorism. Sentsov, the group’s supposed leader, had nothing to do with either attack. Additionally, the nationalist Alexey Chirny acted alone when he tried to acquire enough explosives to blow up a local Lenin monument.

For all the flaws and absurdities of the case against the “Crimean Terrorists,” the suspects in that trial were at least accused of committing and plotting concrete acts. In the “Penza Case,” no one is actually charged with doing anything but belonging to a group.

Why would the FSB need to fabricate criminal cases?

We can only speculate. In October 2017, when the arrests started in Penza, law enforcement were also busy rounding up supporters of the Saratov nationalist Vyacheslav Maltsev, who hoped to stage a “revolution” on November 5, 2017. Many of Maltsev’s supporters have been charged with terrorist offenses, and Maltsev himself fled the country to escape prosecution for allegedly creating a terrorist group.

Federal agents may have originally targeted the “5.11” airsoft team on the suspicion that it was connected to Maltsev’s “revolution.” The suspects themselves have offered two explanations for the name: either it refers to a popular brand of tactical clothing and gear, or it’s the day when the 17-year-old Penza anarchist Nikolay Pchelintsev was hanged in 1907 (there is a memorial at the execution site in the forest outside Penza).

Judging by the case materials, the FSB was particularly concerned about the young men’s possible ties to Ukraine. For example, Viktor Filinkov’s wife, Alexandra Aksenova, moved to Kyiv in the fall of 2017, and he visited her a couple of times. “We can assume that their presence in Ukraine involved a quest for ‘associates’ in either carrying out illegal actions on Russian territory or establishing communication with Ukrainian radicals and possibly with Ukrainian intelligence,” wrote FSB officer Konstantin Bondarev (whom Filinkov accuses of torture).

The exposé aired on NTV identifies Aksenova as the group’s “chief ideologist,” claiming that she tried to create something modeled on the Ukrainian nationalist group “Right Sector,” an organization banned in Russia. Aksenova is now in Finland, where she is seeking political asylum.

Igor Shishkin, who traveled to Ukraine in 2017 to adopt a puppy from a dog breeder he knows, “has ties to representatives of radical groups in Ukraine,” according to the FSB. Shishkin was out walking his dog when Russian federal agents arrested him.

When will the “Penza Case” go to trial? Where will it happen?

The investigation could drag on until the fall or even longer. In mid-June, a court in Penza extended the arrest of six suspects. So far, the criminal cases in Penza and St. Petersburg are being investigated separately, making it possible that the nine men now under arrest will be tried in different cities.

Only a handful of military courts are authorized to hear “terrorism” cases, meaning that the suspects now detained in St. Petersburg could end up in the Moscow District Military Court, and the men jailed in Penza could be tried in the North Caucasus District Military Court — the same court, incidentally, that convicted Oleg Sentsov and his “accomplices.”

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.

This post is also available in: Русский (Russian)

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: