If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.

My Words Have Been Recorded Correctly, an art exhibition in solidarity with imprisoned anarchists and antifascists, took place July 5–7, 2019, at Pushkinskaya 10 Art Center in Petersburg.

The show was sad and daring. During the three days it was up, it was visited by both regular cops and the “anti-extremism” police from Center “E” [known in Russia as eshniki or “eeniks”].

Our group {rodina} [“motherland“] did a performance, and there were concerts and discussions as well. I also had a piece in the show, entitled just one big torture chamber.

I really liked how Jenya [Kulakova] talked about it simply and calmly during her guided tours of the show.

“According to the latest surveys by Levada Center, ten percent of Russians have been tortured.”

True, it’s a really simple figure, but when I hear it I want to hear more figures. What percentage of Russians have tortured someone? What percentage of Russians have ordered someone tortured? What percentage of Russians said nothing although they knew someone was being tortured? What percentage of Russians share a home with people who torture other people at work? Do torturers beat their wives, children, and elderly parents?

At first, I wanted to fashion Russia from a single piece of cardboard, but then I realized I had no sense of how I could unify the country except with borders, frontier guards, and barbed wire. I know tons of different Russias. I know academic Russia and literary Russia. I know the Russia of forests and mushrooms. I know the Russia of poor people and factories. I know the elegant Russia of rich people. All of these Russias have one thing in common: the violence of torture and the fear of torture. So, I assembled the map from scraps of cardboard.

Ms. Apahoncich writing the names of Ukrainian and Crimean political prisoners imprisoned in Russian jails and prisons on the wall below a hand-drawn map of occupied Crimea. Photo courtesy of Ms. Apahonchich

Ms. Apahoncich writing the names of Ukrainian and Crimean political prisoners imprisoned in Russian jails and prisons on the wall below a hand-drawn map of occupied Crimea. Photo courtesy of Ms. Apahonchich

I didn’t know what to do with Crimea. I couldn’t include it since I don’t consider its presence on a map of Russia legal, but I also had no choice but to include it because people are tortured there as well, and the people doing the torturing have Russian passports. So, I drew Crimea on the wall in pencil and wrote a list of Ukrainian political prisoners under it. The list was terrifyingly long.

I spelled the word “torture chamber” as it is pronounced in received Moscow standard [pytoshnaya instead of pytochnaya], although maybe no one speaks that way anymore. I would imagine I don’t need to explain why.

It’s a sad piece. If it were carnival now, I would burn it instead of a straw puppet.

Thanks to Alina for the photographs.

Translated by the Russian Reader. Thanks to Ms. Apahonchich for her permission to translate and publish her post here.

______________________________________________________

[…]Policemen visited the exhibition at the end of its first day. Witnesses said it was the coolest performance in the show. The soloist was Senior Lieutenant Ruslan Sentemov aka Mister Policeman. According to people who took part in the protest action Immortal Gulag, Sentemov insisted this was how the president obliged them to address him when he was detaining them.

The phrase turned into a meme, and Sentemov became the target of parodies and epigrams. It is rare when people are detained at protest rallies in Petersburg and he is not involved. In 2017, 561 people were detained during a protest against corruption. All of them were charged with disobeying the lawful demands of a police officer, and in all 561 cases, that officer was Lieutenant Sentemov. Petersburg civil rights activist Dinar Idrisov claimed each of the ensuing 561 court case files contained a copy of Sentemov’s police ID and his handwritten, signed testimony.

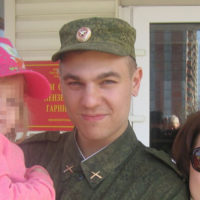

Ruslan Sentemov (right) and another police officer at My Words Have Been Recorded Correctly, July 7, 2019, Pushinskaya 10 Art Center, Petersburg. Photo by Elena Murganova. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

Ruslan Sentemov (right) and another police officer at My Words Have Been Recorded Correctly, July 7, 2019, Pushinskaya 10 Art Center, Petersburg. Photo by Elena Murganova. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

In interviews with the press and when he is on camera, Sentemov likes to maintain the image of a “good cop.” He was true to this image at Pushkinskaya 10 as well, upsetting activists, who surrounded him and peppered him with questions about why he had come to the exhibition.

“This is Russia’s cultural capital. But you, young lady, have a very nasty habit of interrupting people and horning in on the conversation,” he said to one of them.

Reassuring activists he was in no hurry, Sentemov set about perusing the show. The police officer who was with him photographed each exhibit in turn.

Jenya Kulakova volunteered to give Sentemov a guided tour.

“These are drawings made by Dmitry Pchelintsev in the Penza Remand Prison. He was tortured with electricity. Here is a banner with the slogan ‘The ice under the major’s feet.’ Perhaps you are familiar with the music of Yegor Letov and Civil Defense?”

“Perhaps.”

Yegor Letov and Civil Defense (Grazhdanskaya oborona) performing the song “We Are the Ice under the Major’s Feet” at a concert at the Gorbunov Culture Center in Moscow in November 2004. Courtesy of YouTube

“Here is Viktor Filinkov’s account of being tortured, handwritten by a female artist. This is a postcard made by Yuli Boyarshinov. Did you know that, in prison, defendants are prohibited from using colored pencils and pens?”

“No, I didn’t know that, unfortunately. I will probably have to study up on the topic.”

“We have no money and machine guns, but we do have a herbarium of spinach leaves.” Photo by Jenya Kulakov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta.

“We have no money and machine guns, but we do have a herbarium of spinach leaves.” Photo by Jenya Kulakov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta.

“These are drawings from the trials in the Network case. We have an artist who attends the hearings and draws them. This next piece also draws on the case files.”

“I got it. Let’s speed things up.”

“No, you should read a bit of it. Here’s a passage about how someone was hit on the legs and the back of the head. And this is what the tortures said to Viktor Filinkov as they were torturing him. After that, they gave him a Snickers bar to eat. That was probably humane of them, don’t you think?”

“I’ve already read it.”

After strolling around the room containing works by the [Network defendants], Sentemov admitted what interested him most of all was whether the art had been forensically examined for possible “extremism.”

“Look,” said Ms. Kulakova, “all of this was sent to us from remand prisons. By law, all correspondence going in and going out is vetted by a censor. Do you see this stamp here? Have you ever sent a letter to a remand prison?”

“Unfortunately, I haven’t. Or maybe I should say, fortunately. If you say all of this was vetted by the censor, we will definitely have to verify your claim.”

“You seriously want to verify whether remand prison censors working for the FSB have been doing their jobs?”

“At very least, I’d like to send them an inquiry.”

“Here is an installation entitled just one big torture chamber. You may have heard that Levada Center recently did a survey on torture. One in ten people reported they had experienced torture in their lives.”

Jenya Kulakova (center) gives Lieutenant Sentemov and his colleague a guided tour of My Words Have Been Recorded Correctly, July 7, 2019, Pushkinskaya 10 Art Center, Petersburg. Photo by Elena Murganova. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

Jenya Kulakova (center) gives Lieutenant Sentemov and his colleague a guided tour of My Words Have Been Recorded Correctly, July 7, 2019, Pushkinskaya 10 Art Center, Petersburg. Photo by Elena Murganova. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

“Have you been tortured by chance?” Sentemov suddenly asked Ms. Kulakova, staring unpleasantly at her.

“My friends have been tortured,” she replied.

“I was asking about you.”

“Why would ask me about that?”

“You just talk about it so enthusiastically.”

Sentemov appreciated the interest among exhibition goers aroused by his appearance and laughed smugly.

“I think I’m getting more attention than all these pictures,” he said.

He brushed aside questions about what had brought the police officers to the exhibition and how they had heard about it.

“That’s for me to know and you to find out,” he said.

“We gave you a whole guided tour, but you’re just one big mystery,” said Ms. Kulakova disappointedly, fishing for an answer.

“Thank you for such a comprehensive tour. I am quite pleased with the attentiveness of you and your gadgets. Nevertheless, I must leave this wonderful event. I am very pleased you welcomed us so warmly,” Sentemov said in conclusion, turning towards the exit.

“See you soon,” he said as he left.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.

This post is also available in: Русский (Russian)

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: